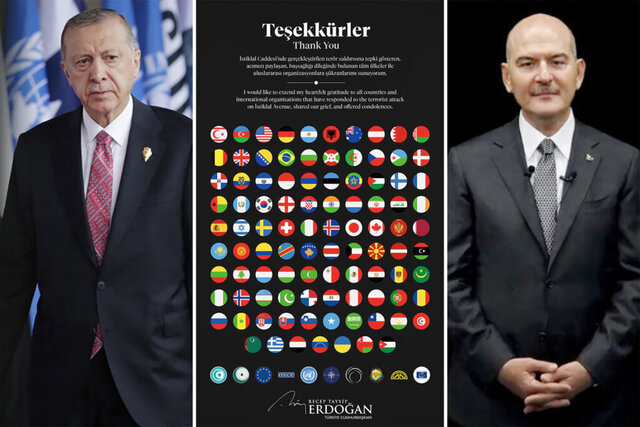

Recently, after a terrorist attack in Istanbul, the Turkish Minister of Interior, Suleyman Soylu, in response to the condolences from the U.S. Embassy, stated that his country did not accept them, transparently suggesting that it was indeed the Americans who were behind this terrorist act.

Shortly after, however, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan posted a thank-you card on his social media pages to those countries that expressed their condolences to his country in connection with this attack. And as you can see, after the flags of Northern Cyprus and Azerbaijan, which are considered almost Turkey, it is the flag of the United States that is depicted on it.

Moreover, at the G20 meeting in Indonesia, Erdogan thanked US President Joe Biden for his condolences. This could be attributed to the difference in approach between Erdogan and Soylu. But then the question arises – how is this possible in the presidential republic that Turkey has been since 2016? Or is Erdogan not in control of the situation in the country? Or is it a game of bad and good investigators for the outside observer?

However, Turkish policy in this direction increasingly resembles a swing and without the extravagant statements of Soylu. To support Ukraine, which has been subjected to Russian aggression, and then to condemn the sanctions imposed by the West against Russia. To express solidarity with Russia by saying that “the West, especially America, is attacking Russia practically without limits” and “against this background, Russia is undoubtedly resisting” and then to vote in the UN that Russia should pay reparations to Ukraine.

As it is now customary to say in such cases, cognitive dissonance arises. If Russia is resisting, why impose reparations on it? And if Ukraine is resisting, why call sanctions aimed at undermining Russia’s aggressive potential an attack on it?

Erdogan’s ability to derive maximum benefit from the contradictions of two partners, providing services to one and then to the other, is well known. But still, one thing is cold pragmatism, and quite another – mutually exclusive angry statements, both by the Turkish leader himself, and by those in Turkey who follow his example.

Whatever one may say, against this backdrop it is impossible not to recall with kind words a much more coherent Turkish foreign policy when it was led by Foreign Minister and then Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu. Unfortunately, Turkey’s current positioning lacks his professorial style, which has been replaced by a bazaar style.