What is the creed of the Russian Federation? And what is its madhhab or manhaj? These questions may seem absurd, since we are talking about a country with a historically predominant non-Muslim population, whose Constitution states: “Article 141. The Russian Federation is a secular state. No religion may be established as state or compulsory. 2. Religious associations are separate from the state and are equal before the law. …. Article 28. Everyone shall be guaranteed freedom of conscience, freedom of religion, including the right to profess or not to profess any religion individually or jointly with others, to freely choose, possess and disseminate religious and other beliefs, and to act in accordance with them….. Article 131. The Russian Federation shall recognize ideological pluralism. 2. No ideology may be established as state or compulsory…. Article 29. Freedom of thought and speech shall be guaranteed to everyone.”

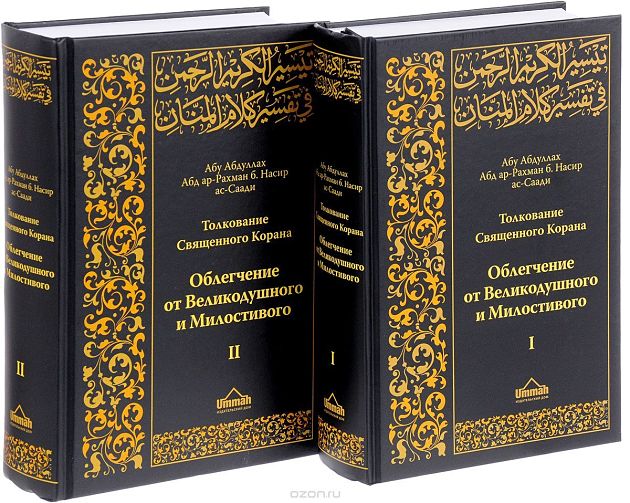

That’s all, formally. In practice, however, the judicial and law-enforcement structures of the Russian Federation persist in deciding which Islamic theological works and translations of sacred texts have the right to exist in it and which do not, as if parodying the role of the Sheikh al-Islam, the Mufti, or the Kadi of the Islamic state with a state-approved ‘aqeedah or madhhab to which all theological works distributed in it must conform. This time, the books “Commentary on the Great Quran Mukhtasar (Abridged) ‘Tafsir al-Quran al-Azim’ by Abu al-Fida Ismail ibn Umar ibn Kaseer al-Dimashqi” and “Abd al-Rahman bin Nasir. Interpretation of the Holy Quran ‘Relief from the Generous and Merciful’: The Conceptual Translation of the Quran into Russian with Commentaries by Abd al-Rahman as-Saadi: in 3 Volumes”. The “muhtasib” of the Prosecutor’s Office of Samara Region will demand their banning at the session of the Krasnoglininsky District Court of Samara, which is scheduled for January 21 this year. Well-known Muslim lawyers and human rights activists Ruslan Nagiyev, Said-Magomed Chapanov, Ravil Tugushev and Marat Ashimov will defend the interests of the publisher (and, in fact, of Muslims) in court.

Another interesting point that some observers have pointed out is that the “guardians of the state ‘aqeedah of the Russian Federation” once again want to ban the translation of a theological text by a well-known translator and Islamic scholar (a real one, unlike Silantyev and company) Elmir Kuliev. Previously, they had already banned his works such as “Zakaat. Its Place in Islam. Fasting in Ramadan, its meaning for Muslims”, “On the Path to the Koran”, and even “The Conceptual Translation of the Holy Koran into Russian”. The reasons for such “love” for Kuliev can only be speculated, since this person is known for his calls to Muslims not only to live peacefully in the states of which they are citizens, but also to refrain from any activity that could cause dissatisfaction with the state. However, as we can see, in the case of Russia, the translation of the Holy Book of the Muslims or the writing of texts on general theological topics can serve as a reason.

Nevertheless, it should be noted that Kuliev has opponents among Muslims on purely theological issues. But what does the Prosecutor’s Office of the Russian Federation have to do with this? Or does it adhere to some ‘aqeedah, madhhab, or follow the fatwas of a certain mufti, from which deviations are unacceptable? Can they then be expressed to the wider public? But if we are serious, the formal basis for banning Islamic literature is supposed to be the presence of extremism in it, not its “deviation from the correct ‘aqeedah”. But if the recognition of the works of ideologues of contemporary uncompromising groups as extremist is easily explained, the attempt to attribute extremism to translations of sacred Muslim texts – the Qur’an, collections of authentic hadiths, or classical theological works (an analog of the patristic tradition in Orthodoxy) – seems to be a prohibition of Islam.

No wonder that even such an absolutely internal system person as Ramzan Kadyrov reacted sharply to such an attempt several years ago. But, apparently, the Russian authorities believe that “water wears away stones,” and sooner or later those who consider themselves Muslims within this system will come to terms with these endless bans. For some of them, however, it may sooner or later become a reason to think about how long they can sit on two chairs – their Islamic identity and their loyalty to a system that fights against it and everything it deems appropriate. After all, 10-15 years ago, some of the flags did not consider it possible to change. For example, one of the preachers of foreign origin, around whom Muslim youth gathered in a large Russian city, told the author of these lines that the Russian law enforcement officers who came to “talk” with him warned him that he could teach his students everything except one thing – not to call for jihad against Russia. When he objected that he could not ignore the verses and hadiths on jihad, they replied that they understood that, but asked him not to use them to call for jihad “here and now,” which he avoided.

However, step by step, by testing Muslims, this system saw that they could prohibit anything without any consequences for themselves, and finally reached the point of prohibiting translations and universally accepted interpretations of the Quran, Hadiths, booklets on Zakat and collections of prayers (Dua), and so on. Isn’t it time for Muslims to demand that they adhere to their own official “manhaj” in the form of constitutional provisions on freedom of religion, speech, and ideological pluralism?