If we try to periodize the foreign policy of Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s long rule, we can identify several main stages. The first, initial period is quite logical for a government that is just beginning to establish itself both domestically and internationally – this policy is called “zero problems with neighbors” and is accompanied by a rapprochement with the EU, the stated goal of which is Turkey’s accession to the EU. This period is from Erdogan’s coming to power to the beginning of the Arab Spring, and it must be said that it was during this period that Turkish foreign policy was the most realistic and successful, as it was based on achievable goals. Accession to the EU is not one of these goals, but by declaring this goal, the AKP leaders hardly believed in its achievability – rather, it was necessary for Turkey’s political and economic modernization in cooperation with the EU, which was successfully achieved.

The second period is the pursuit of ambitious tasks within the framework of a new strategy known as “neo-Ottomanism”. It should be noted that this term itself is flexible and can have different, sometimes mutually exclusive, meanings. For example, Ahmet Davutoglu, who is considered the ideologist of neo-Ottomanism and served as Turkey’s foreign minister from 2009 to 2014 and prime minister from 2014 to 2016, also advocated the principle of “zero problems with neighbors” in the initial stage. However, it is evident that Turkey’s foreign policy under his leadership since the beginning of the Arab Spring has been characterized by maximum problems with neighbors. This was the result of the project to transform Turkey into the center of Sunni political Islam, including by supporting anti-Assad Sunni rebels in Syria and Sunni Kurdish and Arab forces in Iraq. It was during this period that many Islamic forces began to look to Turkey as a new hope for the Islamic Ummah, not only in the Turkic region but also beyond. This was actively encouraged by the Turkish leadership, which declared Turkey as the defender of the oppressed, the second homeland for every Muslim, and so on. This policy was strongly opposed by two immediate regional competitors – Iran and Russia – and did not receive any real support from the West, which was the hope of the first period described above. Its culmination was the incident of the downed Russian plane and the Russian army’s attack on Aleppo in 2015, which threatened a direct Turkish-Russian military conflict. At the same time, it became clear that Turkish society, for the most part, was not willing to pay the price demanded by the strategy of restoring the Ottoman caliphate in a soft form or, in other words, affirming Turkey as the leader of the Sunni world. This is evidenced by the significant opposition to this policy within Turkey, both from the open opposition and the so-called “parallel state,” numerous economic lobbies interested in cooperation with Russia, and growing discontent within Turkish society over the influx of Arab refugees. Moreover, in our view, Turkey missed the most opportune moment to implement this strategy when Russia was distracted by the annexation of Crimea and the war in eastern Ukraine, which theoretically gave Turkey the opportunity to behave similarly in Syria. However, the question is whether Erdogan had the power resources to behave in such a way in 2014, given the presence of opposition elements in the army…

The third period of Erdogan’s foreign policy begins with the dismissal of Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu and is consolidated after the failed coup of July 2016. This period is characterized by the abandonment of the pan-Sunni (pro-Iranian) strategy of neo-Ottomanism and a shift to a position of national sovereignty and economic pragmatism. This period includes the reconciliation and rapprochement with Russia and Iran, the alliance of Erdogan’s party with its former opponents from the Nationalist Action Party, the recognition of the Shiite rule over Iraq and support for it in the conflict with Iraqi Kurdistan (which was criticized by the retired Davutoglu), the practical recognition of the control of the Assad regime, supported by Russia and Iran, the practical recognition of the Assad regime’s control, supported by Russia and Iran, over most of Syria’s territory in exchange for its agreement to the military operation of Turkey and its proxy against the Kurdish communist forces (PYD-YPG) acting under the auspices of the USA (the previous Obama administration), thus limiting Turkey’s sphere of influence in Syria to the enclave in the northeast (“Euphrates Shield” + “Olive Branch” + Idlib), where the rebels from the rest of the country began to be evacuated. In addition, the rehabilitation of Mustafa Kemal’s legacy, including attempts to give it Islamic legitimacy, and closer ties with China and its ruling Communist Party are forming in this period. It must be recognized that objectively, during this period, Erdogan was able to maintain and strengthen his power inside the country and normalize his position in the region by abandoning the pretensions of the previous stage, reduced to mere rhetoric, and obtaining modest Turkish protectorates (with uncertain status and prospects) in northeastern Syria. However, it should be noted that during this period, Turkey’s relations with the West have deteriorated significantly, whether it is the conflict with the US over the purchase of S-400s, the issue of Manbij, Gulen, etc., or with the EU, with which integration has practically been stopped.

So, three stages. In recent months, however, there are reasons to speak of the beginning of a new stage in Turkish foreign policy – an intensification in the direction of the Mediterranean. There are at least three recent events that point to this.

The first is Ankara’s successful support for the Government of National Accord in Libya, which led to the failure of Khalifa Haftar’s adventure, as we wrote recently.

Secondly, yesterday’s statement by the Russian Foreign Ministry expressing concern over Turkey’s actions in the disputed Turkish-Cypriot waters, in particular the entry of another Turkish vessel for geological exploration. The statement refers to this disputed area as the “exclusive economic zone of Cyprus” and Turkey’s actions in it as “a violation of the economic sovereignty of Cyprus,” indicating whose side Moscow is on in this dispute. Earlier, Greece was supported by the EU summit, which recognized Turkey’s actions as “illegal drilling activities” and promised to “respond appropriately” if they continued. Ankara, however, has declared that it will continue to exploit the resources of the waters it considers its own.

Third, the Forum for Cooperation of Southeast European Countries, of which Erdogan is the key figure, began yesterday in the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina and continues today. The composition of this forum and the accompanying events are quite interesting. For example, representatives of Kosovo were not invited to the forum, but among the co-presidents of Bosnia and Herzegovina there was a representative of the so-called “Serbian Republic”, Milorad Dodik. One thing clearly followed another, which Dodik noted, praising Erdogan for fulfilling his promise not to hold such a forum in Kosovo and not to invite representatives from there, which apparently allowed the Serbs to participate. Thus, Ankara preferred the participation of Serbs to that of Kosovo Albanians, which seems quite strange from the point of view of Islamic solidarity. However, in addition to the pragmatic reasons (Turkish-Serbian projects) that may explain this, there may also be a political-ideological component. Specifically, one of the main issues mentioned by Erdogan himself and his interlocutors (especially Dodik) was the fight against the Gulenist movement in the region, the absence of which (to the extent expected by Turkey) Ankara is dissatisfied with Pristina. Some attribute the incident in which Erdogan’s security refused to be checked by the Bosnia and Herzegovina Border Service at the airport to the intelligence activities of the Gulenists. In this regard, the head of the Border Service, Zoran Galic, publicly protested, for which he was immediately labeled by some pro-Erdogan sources as an agent of the Gulenists who are deliberately harming Turkish-Bosnian relations.

The combination of these actions in the direction of the Mediterranean does not look like a coincidence. In this regard, some commentators speculate that after a period of forced isolation within the framework of the “Turkey as a besieged fortress” strategy, Erdogan has decided to reintegrate his country into the broader world politics, betting on transforming it into one of the main Mediterranean powers. Of course, this will not be a return to the policies of the second stage, as the policies of the supposed fourth stage will be based on different foundations. It will be based primarily on pragmatic calculations, i.e. the struggle for natural resources and advantageous logistics (supply routes) for Turkey’s developing economy. The ideological component of this policy, if it is to be expected at all, will be more of a pleasant bonus, as it is in Libya. Moreover, the ideological component here will be more “party-based” than generally religious – in Libya, the main struggle is between Turkey, which supports the GNA, and the UAE and Egypt, which support Haftar. In the Balkans, as we can see, it is easier for Erdogan to find common ground within this policy with Dodik, who is ready to take up his rhetoric against the Gulenists, than with the Kosovars, whom he suspects of having links with them.

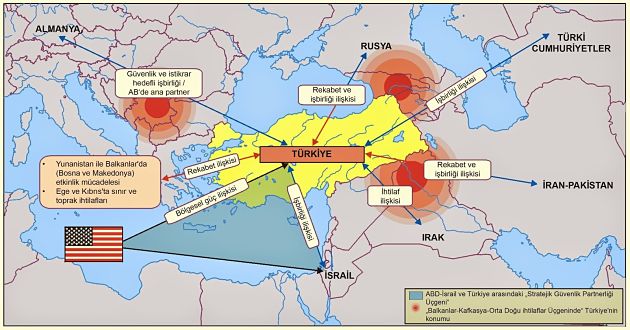

Turkey objectively has a chance to succeed in the Mediterranean, and one of its main arguments is its powerful navy. On the other hand, it should be understood that the Mediterranean Sea, which has been the center of the world’s leading civilizations for several thousand years, is a prize as desirable as it is fraught with enormous risks. Turkey can count on the fact that Greece is a weak opponent and that the EU and NATO are currently unable to come to its aid. Such a bet paid off once, during the Cyprus conflict, and it is not impossible that it could do so again. However, changes in the geopolitical situation should be taken into account – during the Cyprus conflict Turkey was needed by the West as an ally to contain the USSR, while now, especially in connection with Ankara’s purchase of S-400s from Russia, Turkey’s status as a member of the North Atlantic Alliance is openly questioned. Moreover, Russia is unlikely to support Erdogan in the Cyprus dispute. In Libya, Kremlin-linked actors (the Wagner group) are also playing on the same side as the French against Turkey, and Moscow and Ankara have recently had difficulty finding common ground in Syria.

Thus, there is a risk of the emergence of a broad anti-Turkish coalition in the Mediterranean, including Greece, Israel, NATO with Russia, and Egypt as an ally of Saudi Arabia, while it is currently unclear whose support Ankara can count on in this confrontation. On the other hand, Erdogan is an experienced politician who has repeatedly demonstrated his ability not only to raise the stakes in the game, but also to withdraw from it with a profitable retreat at the right time. Let’s see what happens this time.