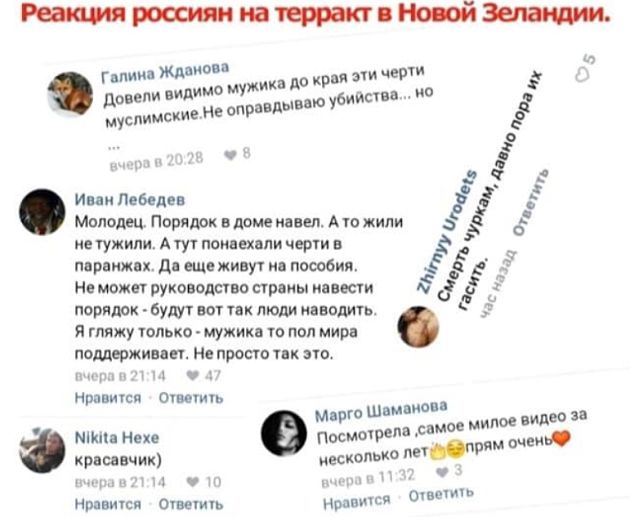

The reaction to the shooting at a mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand, reflected in thousands of comments by many of their fellow countrymen, came as an unpleasant, if not shocking, surprise to many Muslims. Although, to be honest, this event falls under the category of “it’s never happened before and here we go again. It’s time to get used to the fact that Russian society is not characterized by special empathy, let alone love, for Muslims. And compared to the reactions of New Zealanders, who showered the mosque with flowers or greeted the news with tears in their eyes, it’s mainly the former. One can certainly not love Muslims, but objectively, the value of a single human life is different in New Zealand, where fewer people are killed in a year than a scoundrel killed in a mosque in a day, and in Russia, where heinous murders or child abductions appear regularly in crime reports.

But there is no need to have illusions about the “foreign” reaction. There were enough people in other countries who, upon hearing this news, if not with open approval, at least with glee. But what conclusions should be drawn from this, and what should not?

If a person has illusions that many of the people among whom he lives and with whom he interacts on a daily basis are kind and smiling, and at most wish death not to him personally but to his fellow believers and loved ones, or at least will not feel any regret about it, then such an insight would be very useful. At least because such a person will begin to soberly assess his position in this society and evaluate his prospects and risks accordingly.

What we want to warn our fellow believers against, however, are emotional reactions and conclusions in this regard. They will bring no good to those who succumb to them, nor to Muslims in general, and may even contribute to the achievement of our enemies’ goals.

First of all, regarding the double standards in such reactions, when it comes to Muslims and non-Muslims, it is necessary to understand that they are natural. As the saying goes, “Charity begins at home,” and every person will always sympathize with his own first, and only then, at best, with strangers. This is what we Muslims do when we react first and foremost to the misfortunes of our fellow believers. Moreover, let’s be honest, even in the case of events within the Ummah, this reaction will vary, and people will primarily take to heart what affects them, their fellow countrymen, compatriots, those in similar situations, and so on. Whether this is true or not, it is a characteristic of human psychology and social psychology that must simply be accepted as a fact.

Secondly, yes, we need to understand how the society in which we live (and not only Russian society) functions, what its priorities are, and what ideas and communities hold the leading positions. Both in the West and in Russia, a secular civilization of so-called Judeo-Christian dominance prevails, to which Islam and Muslims are at best alien and at worst openly hostile. To be surprised or outraged about this is the same as being surprised and outraged that the sun burns on a hot summer day and that it rains in the fall – one must accept it as a fact and draw appropriate conclusions. For example, in the summer, wear a hat, try not to stay in the sun unnecessarily, and drink more fluids; in the fall, take an umbrella, wear waterproof clothes and shoes, and so on.

However, a separate question regarding this so-called Judeo-Christian dominance is how its first component, historically hated even more than it is today, managed to attach itself to the second and be accepted on board, especially as an honored, if not privileged, passenger. This is an interesting and highly relevant question for Muslims, but it is necessary to remember how long it took, what preceded it (even in the last century), and what price was paid in all respects.

Third, it is necessary to understand that the aversion of at least a significant part of non-Muslims to Islam and Muslims is objective for two reasons. The first reason is spiritual, and Muslims should be well aware of it from the Qur’an. But there is a second reason – it is not only the image that its enemies create of Islam and Muslims, but also the image that many Muslims themselves create, as a result of which many people who were not initially prejudiced against Islam become its enemies.

It is not certain whether to believe the words of New Zealand Muslim killer Brenton Tarrant, but at least in his manifesto he wrote about his motivation for this crime as a thirst for revenge against Europeans who were victims of attacks by ISIS supporters in Europe and Australia. Another of his fellow crusaders, Anders Behring Breivik, wrote in his book that he came to his ideas under the influence of racially and religiously motivated criminal lawlessness by Pakistani immigrants in Norway.

Yes, it is clear to us that neither the first nor the second represent Islam or normal Muslims, just as Tarrant and Breivik do not represent Christianity or normal Europeans. Yes, we must understand that these problems in the Muslim world, the fruits of which are now being reaped not only by Muslims themselves but also by Europeans, are largely the result of the destruction of Islamic civilization and statehood, the imposition of anti-Islamic regimes, and the struggle against any healthy Islamic forces and alternatives. But we must also understand that these fruits are not only reaped by non-Muslims, who prefer not to delve into the reasons for this, but these phenomena worsen our situation in our environment even more. What to do about it is another serious question. But it is clear that what we should not do is to react to such events in a way that makes our situation even worse.

In particular, we must not stir up waves of accusations and allegations that will drive weak minds and souls in our community to destructive (for us) conclusions and actions.

While we pay tribute to our victims – may Allah accept their martyrdom – sincerely sympathize with them, and help their loved ones as much as possible, we must learn to think and act as soberly as possible in public and inter-community relations. Our expectations should be focused on achieving realistic goals – not that everyone will love us, but that our rights, starting with the right to life and security (which we must think of ourselves), will be secured, for which, in a non-Islamic environment, a functioning legal state and civil society are necessary through which this can and must be achieved.

Without harboring any illusions about how we are treated and drawing sober conclusions from this, we must be aware of our responsibility for this and learn not to increase the number of our enemies but to reduce it by turning enemies into friends or at least opponents or interlocutors.

Muslims living in non-Islamic societies should adopt this approach. And for those who are fortunate enough to live in an Islamic society, they should remember that they are also responsible for it, because today there is not a single Muslim country that could and would accept all these people, and we can see the result of attempts to create one all at once, in Baghouz.

-banned in Russia and most countries.